TEA at the People of Color Conference: The Constructive Adversity of Talking About Race

Words by Carolyn Highland

I was sitting in a room full of nearly a thousand white folks at the National Association of Independent Schools’ (NAIS) People of Color Conference (PoCC), feeling distinctly uncomfortable. We were at our first “Affinity Session”–a time for people to come together with others who shared their racial identity.

Why was there a room full of white people at a conference designed for people of color? Because tackling the systemic racism our country was founded on and functions within today requires white allyship. I felt nervous and unsure about my place at PoCC, but also energized and driven to learn and grow. I felt the way we all often feel in the face of a new or challenging experience.

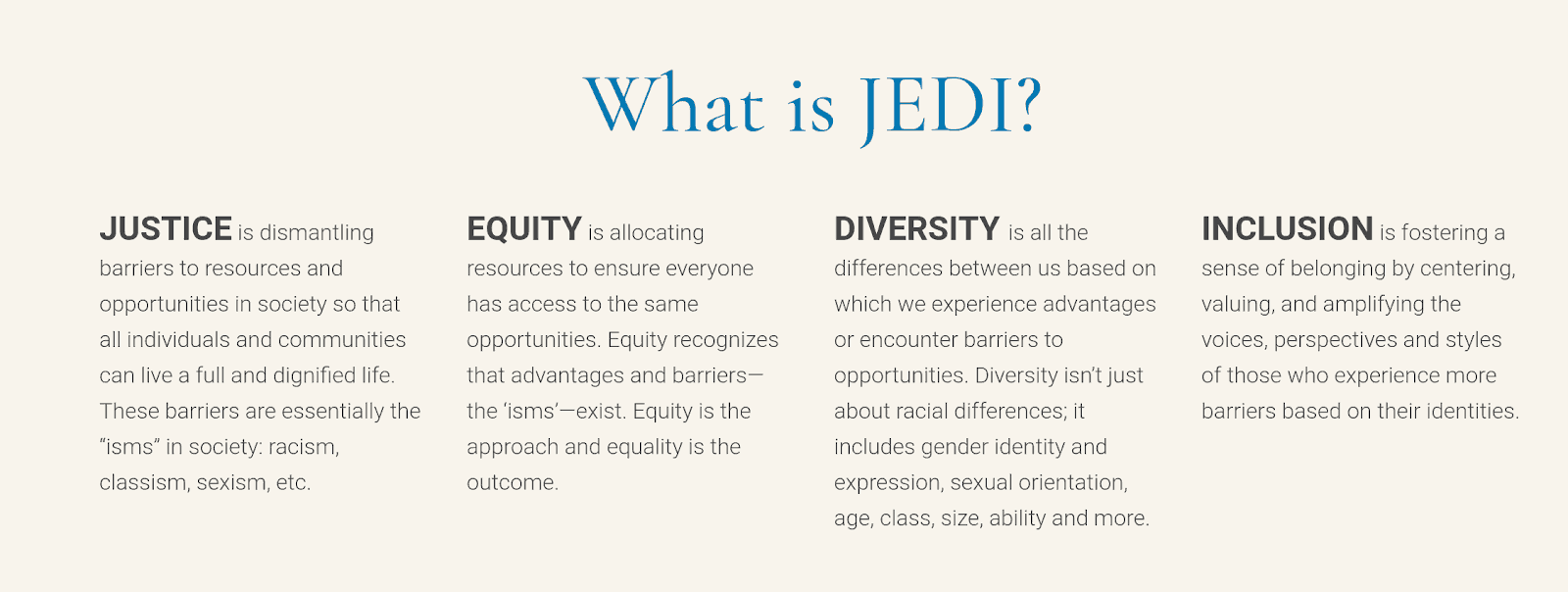

The woman next to me recounted a tale of a white colleague at the conference who had been told by a person of color, “I hate that we need you here.” This comment stayed with me throughout the three days we spent in Seattle–as white folks, we were in a space not designed for us, but our allyship was also required to be successful in justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion (JEDI) work in schools and in society. Why? Because as white folks living in a society that has been created to benefit us over others, we hold immense power to create change.

The facilitators of the Affinity Session described white folks’ role in JEDI work as complicated and difficult, but necessary. Complicated and difficult, but necessary. To me, it sounded a lot like how we describe constructive adversity.

Matt Morrison, Beth Vallarino (Middle School Humanities), and I were attending the conference as part of TEA’s commitment to JEDI work. We wanted to see how other independent schools were ensuring an equitable and inclusive environment for students, families, and faculty of diverse backgrounds, and how they were galvanizing white allies to work for a better future for everyone.

Over the course of three days, we would attend workshops, listen to keynote speakers, and participate in affinity sessions. We would be pushed outside of our own comfort zones, we would hear impactful stories, we would be exposed to paradigm-shifting resources and frameworks. We would experience constructive adversity through taking a hard look at our own racial identities and how those identities affected our lived experiences and the lived experiences of others.

Independent schools are often centers of privilege, and with that designation comes a certain level of social responsibility. Pedro Noguera, Ph.D, one of the keynote speakers at PoCC, said that education either upholds systems of oppression (set of processes, actions, and ideas creating a system that are built around the superiority of some and the inferiority of others) or dismantles them. That there is no such thing as a “neutral” school–if no work is being done, the status quo is being reinforced. He finished his talk by saying that the number one barrier to progress is complacency.

During a workshop called “Who We Are: Racial and Ethnic Identity Development for Educators and Youth,” our facilitator talked about the fact that people of color typically become aware of their racial identities early on in life, and out of necessity, whereas white folks can all too easily go their entire lives without doing any racial identity work at all. She also said that it’s never too early to start talking about race with kids–and that often, they handle it much better than adults do.

I realized throughout this workshop that as white folks, we are not socialized to have conversations about race. We are socialized to do what’s easy–to pretend like race doesn’t exist, to ignore how our whiteness affects others. What I began to realize was that if TEA wanted to be a safe and inclusive space for people of color, we needed to start teaching white adults and children about their own racial identities, and how to have meaningful conversations about race. We needed to start doing what was difficult.

In August of the 2019-20 school year, Taylor Simmers asked us how we could increase opportunities for constructive adversity in the classroom. How could we bring the same type of learning that happens on a backpacking trip in the rain or the first time on cross-country skis or collaborating to set up a tent, inside?

It seemed we had at least one answer. Doing our own racial identity work in order to facilitate students doing the same would be a challenging, potentially uncomfortable, emotional experience. It would require adults and children to expand the parameters of their thinking, to shift their paradigms, to look inward. It would require trial and error, collaboration, curiosity, critical thinking, problem-solving, bravery, humility, empathy, and perseverance. It would, in short, require them to do everything that TEA is all about.

Matt, Beth, and I left PoCC feeling energized, driven, and inspired. We left feeling the buzz that comes with being in a room filled with 7,000 educators and students dedicated to social justice– to a better future for all people. We left with a real-world problem in our hands that we know our incredible faculty, staff, and students are capable of working toward solving.